GCShutter

State of the REIT Nation

In our State of REIT Nation report, we analyze the recently released NAREIT T-Tracker data. Earlier this month, we published our REIT Earnings Recap which analyzed Q2 results on a company-by-company level, but this report will focus on higher-level macro themes affecting the REIT sector at large.

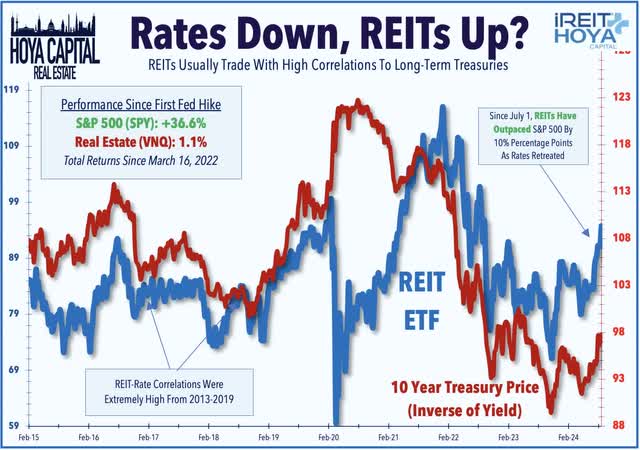

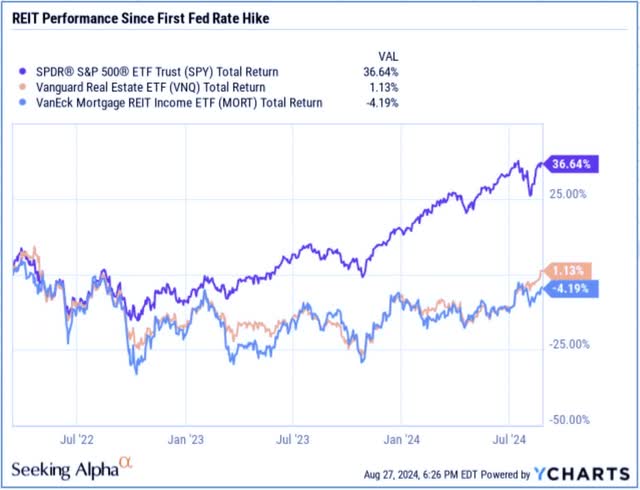

Rates down, REITs up? Two years of persistent rate-driven pressure on the residential and commercial real estate market appears to finally be abating as the worst of pandemic-era inflationary pressures subside. Commercial and residential real estate markets have been an easy transmission mechanism – or “punching bag” – of the Federal Reserve’s historically swift monetary tightening cycle, which resulted in the largest increase in the Federal Funds rate in any two-year period since 1981 on an absolute basis and the single-most significant increase on a percentage basis. Concern about real estate is warranted given that the two prior rate hike cycles that exceeded 400 basis points – the late 1980s cycle that sparked the Savings & Loan Crisis and the mid-2000s cycle that sparked the Great Financial Crisis – resulted in significant distress and disruption within in the real estate industry. This concern has resulted in a nearly one-to-one correlation between REIT valuations and benchmark long-term interest rates since the end of the GFC period.

From the start of the Federal Reserve’s rate hiking cycle in March 2022 through the unofficial start of the “Fed pivot” in early July 2024, the Vanguard Real Estate ETF (VNQ) posted historical levels of under-performance relative to the broader S&P 500 (SPY) – 45 percentage points – which far-exceeded the underperformance of the REIT sector in any prior two-year period, including the Great Financial Crisis. Before the shift in Fed policy expectations in early July – a pivot sparked by a series of weak employment reports and further evidence of normalizing inflation conditions – the real estate sector (XLRE) was far and away the weakest-performing of the 11 GICS equity sectors – far weaker than even other “bond alternatives” like Utilities (XLU). Since the “pivot’ in early July, however, the REIT Index has outpaced the S&P 500 by 10 percentage points, during which time the benchmark 10-Year Treasury Yield has declined by roughly 60 basis points from around 4.50% to 3.90%. Even with this recent outperformance, REITs still have nearly 35 percentage points of “catch-up” to do with the S&P 500, if past performance patterns between the REITs and equities persist.

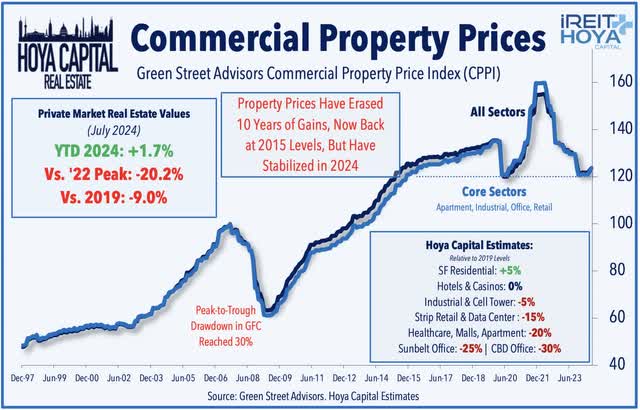

This ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ comes as commercial property values were approaching the critical 20% drawdown level – a level that can result in cascading distress that extends beyond the weakest players. The business models of many private equity funds and non-traded REITs were not simply designed for a period of sustained 4%+ benchmark rates, nor for a period of double-digit percentage point declines in property values. Green Street Advisors’ data shows that private-market values of commercial real estate properties have dipped 20.2% from the peaks last April, but have stabilized in recent months, posting a +1.7% increase this year. By comparison, the peak-to-trough drawdown in this valuation index during the Great Financial Crisis was 30%. We’ve noted that the 20-25% drawdown level is a critical “capitulation threshold” – a level that matches the maximum Loan-to-Value (“LTV”) ratio accepted by conventional commercial real estate lenders. While every property sector has seen a rate-related valuation hit, the troubled office sector has, of course, seen the most significant valuation declines of 30%+.

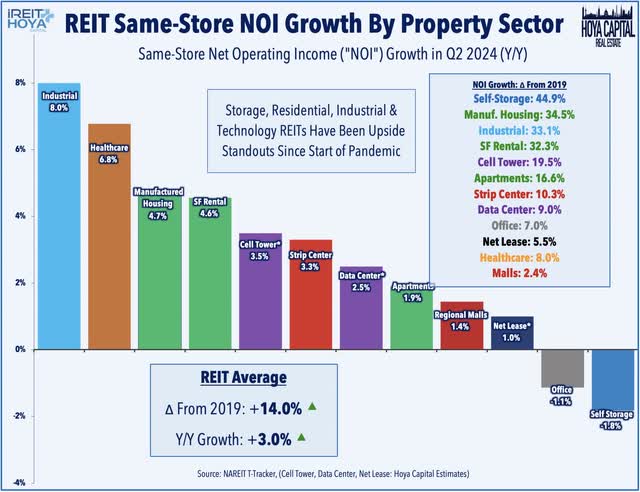

On that point, it’s critical to stress that this valuation pressure – and the pockets of distress that emerged in recent quarters – have remained almost entirely interest-rate-driven (with the notable exception of the office sector). Resilient property-level fundamentals are the major reason that we haven’t seen a more material increase in distress in non-office sectors. Fundamentals remain solid-to-strong across nearly every property sector, with the notable exception of coastal office properties. Public REITs reported that “same-store” property-level income, on average, was 14.0% above pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter. The residential, industrial, and technology sectors have been the upside standouts throughout the pandemic, with most of these REITs reporting NOI levels that are over 20% above 2019 levels. Even the battered office REIT sector has posted positive 7% growth in property-level cash flows since 2019 as tenants in long-term leases continue to pay rents. Retail REITs – which had seen sharp declines in property-level cash flows early in the pandemic due to missed rent payments – have posted some of the more impressive property-level performance in recent quarters, while Senior Housing REITs have also enjoyed a swift NOI rebound this year.

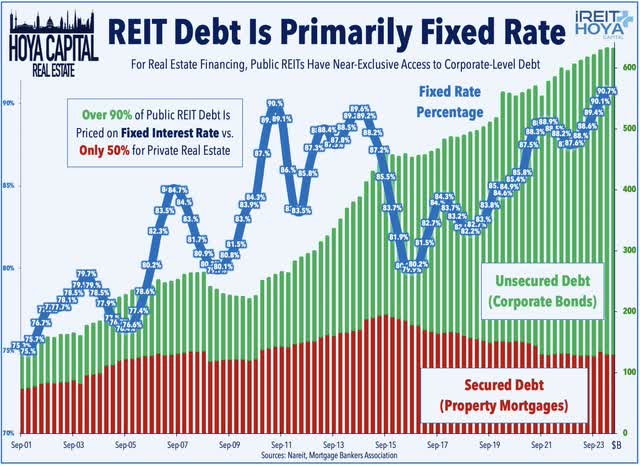

Of course, the interest rate headwinds become very “real” when the underlying properties are financed with debt – particularly copious amounts of variable rate debt. With the scars of the Great Financial Crisis still visible, most public REITs were “preparing for winter” for the last decade, often to the frustration of some investors who turned to higher-leveraged and riskier alternatives in recent years. Private market players and non-traded REIT platforms were willing to take on more leverage and finance operations with short-term and variable-rate debt – a strategy that worked well in a near-zero rate environment but quickly crumbles when financing costs double or triple in a matter of months. Nareit reported earlier this year that nearly 50% of private real estate debt is priced based on variable rates, compared to under 10% for public REITs. We’ve observed significant pain inflicted on the handful of public REITs that entered this period with variable rate debt loads in the 20-30% range – still relatively low compared to typical private equity firms – resulting in double-digit percentage point drags on Funds from Operations (“FFO”).

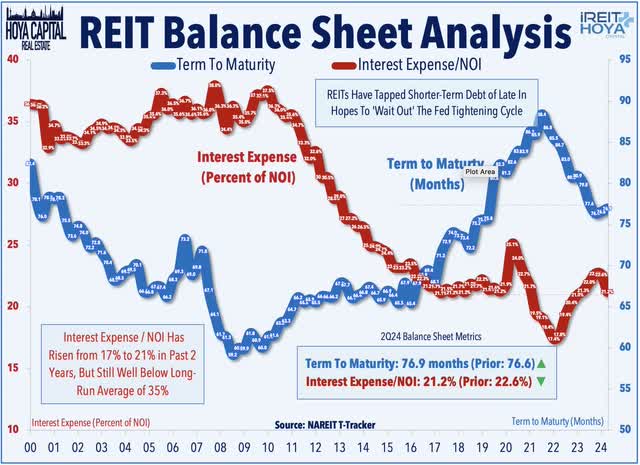

Access to long-term debt is perhaps the most distinct competitive advantage of the public REIT model, but it’s an advantage that hardly gave public REITs much of an edge when debt capital was cheap and plentiful in the “zero-rate” economic environment of the 2010s. Compared to private institutions, publicly-traded REITs had far greater access to fixed-rate unsecured debt – which is usually in the form of 5-10 year corporate bonds. This allowed REITs to lock-in these fixed rates on 90% of their debt while simultaneously pushing their average debt maturity to nearly 7 years, on average, thus avoiding the need to refinance during these highly unfavorable market conditions. Even with the significant pullback in financing activity in recent months, the average term-to-maturity for public REITs is still over 6 years – well above the pre-GFC highs of around 4 years – and significantly above the weighted average term-to-maturity of around 3 years for private real estate assets. Hence, for many of the highly-levered players that lacked access to long-term capital, the trends observed in the chart below are magnified by a factor of 2-3x.

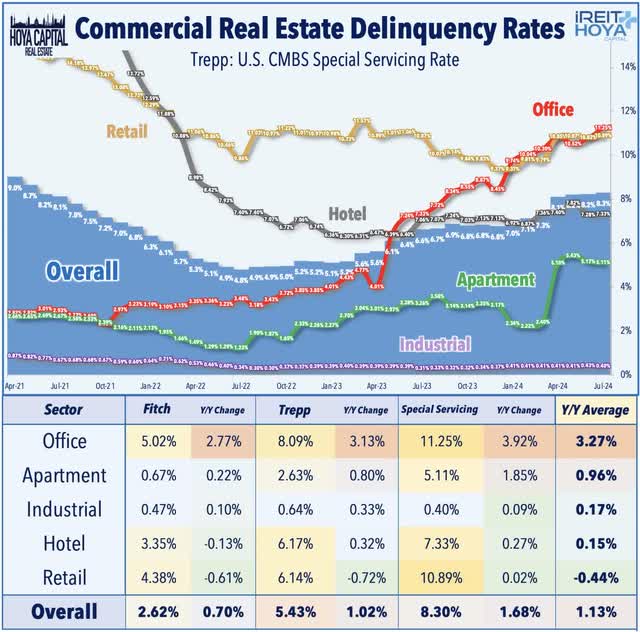

Not out of the woods, yet. “Hope” has been the only strategy for many highly-levered property owners amid a dearth of buying interest and limited capital availability – “hope” that interest rates recede before their “debt clock” expires. The Mortgage Bankers Association’s 2023 Loan Maturity Survey showed that roughly 20% of commercial mortgages mature by the end of 2024 and roughly 50% by the end of 2025, so the clock is still ticking ever louder for the firms sitting on a significant pool of variable rate debt, and it’s beginning to show-up in delinquency rates. Trepp reported last month that the overall commercial real estate delinquency rate rose to 5.43% – up 100 basis points from last year to the highest level since December 2021. Office delinquencies have accounted for the vast majority of this increase, however, surging nearly 3x from a year ago to 8.09% – the highest since November 2013 – and up very sharply from the record-lows in 2021 of 1.75%. Apartments are the only other major property sector that has seen a material increase in delinquency rates in recent quarters, a direct result of the high variable rate debt utilization rate given its relative ownership skew towards smaller “mom and pop” investors.

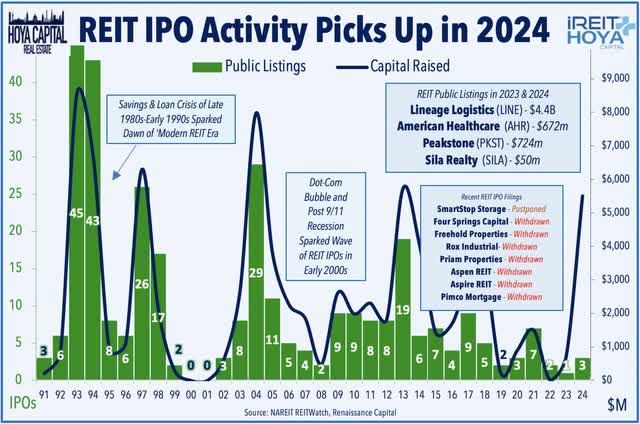

While REIT stock prices don’t yet reflect it, macroeconomic conditions are evolving in an ideal manner for public REITs to finally exploit their competitive advantage – access to nimble equity capital and long-term fixed rate debt – which was of little advantage in the “lower forever” environment. And while past periods of significant tightening were remembered as those of distress, they can rightfully also be remembered as periods of a significant revolution and rebirth that spanned many of the public REITs that exist today. The S&L Crisis of the late 1980s – which resulted in the failure of nearly a third of community banks and resulted in significantly constrained access to debt capital – spawned the dawn of the ‘Modern REIT Era.’ A second wave of REIT IPOs followed in the aftermath of 9/11 and again after the Great Financial Crisis as the limited access to (and high cost of) debt capital, combined with a lift in equity market valuations of public REITs – pushed otherwise distressed highly-levered private portfolios into the public equity markets, a theme that we could very well see repeat over the coming quarters.

Deeper Dive: REIT Fundamentals

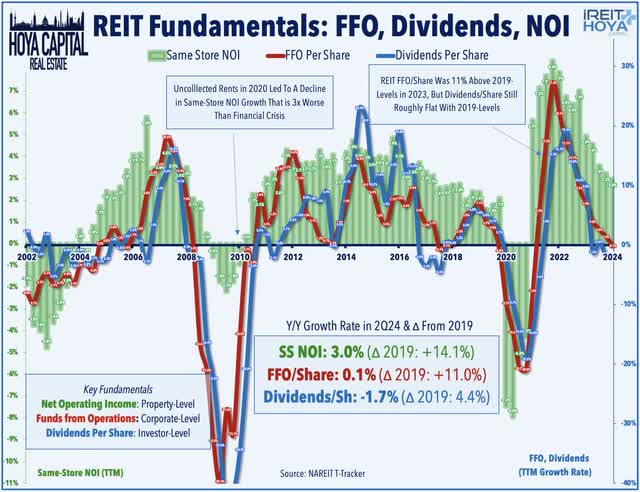

As noted, the pockets of distress are almost entirely debt-driven – and further isolated to the office sector – as nearly every property sector reported “same-store” property-level income above pre-pandemic levels. REIT company-level metrics have tracked this rebound in property-level performance relatively closely throughout the pandemic – with the exception of the highly-levered REITs that expect sharp FFO declines this year even as property-level cash flows continue to increase. REIT FFO (“Funds From Operations”) has fully recovered the sharp declines from early in the pandemic, and in the second quarter, FFO was 20% above its 4Q19 pre-pandemic level on an absolute basis, and roughly 11% above pre-pandemic levels on a per-share basis. On a year-over-year basis, FFO/share was up 0.1% in Q2. Same-store Net Operating Income (“NOI”), meanwhile, was roughly 3.0% higher on a year-over-year basis in the second quarter, and 14% above the pre-pandemic level.

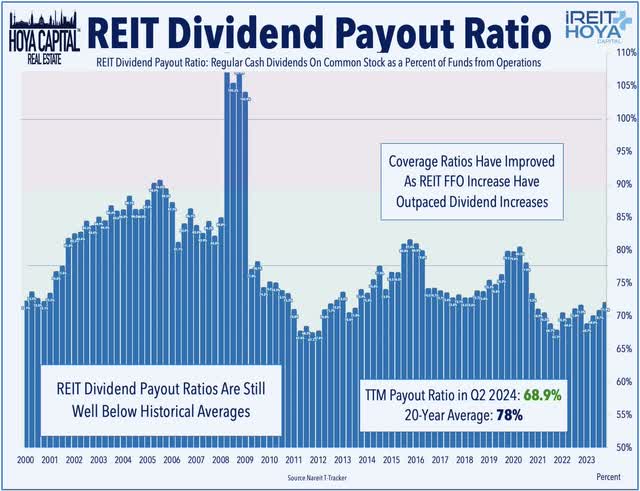

Powered by more than 120 REIT dividend hikes in both 2021 and 2022 – and another 80 dividend hikes in 2023 – dividends per share have finally fully recovered from the wave of pandemic-era dividend cuts in 2020. In 2024, we’ve tracked 60 dividend increases, while 15 REITs have reduced their dividends. With FFO growth significantly outpacing dividend growth since the start of the pandemic, REIT dividend payout ratios remained at around 70% in Q2 on a trailing twelve-month basis – well below the 20-year average of around 80%. With a relatively low dividend payout ratio, the average REIT has built up a buffer to protect current payout levels if macroeconomic conditions take an unfavorable turn. As always, the sector average does mask some elevated payout ratios across several sectors: Mortgage REITs currently pay out about 95-100% of EPS, on average, while Cannabis REIT payout ratios are also elevated. Other higher-risk sectors have built up a decent buffer, as office REITs pay just 70% of FFO while hotel REITs pay less than 40%.

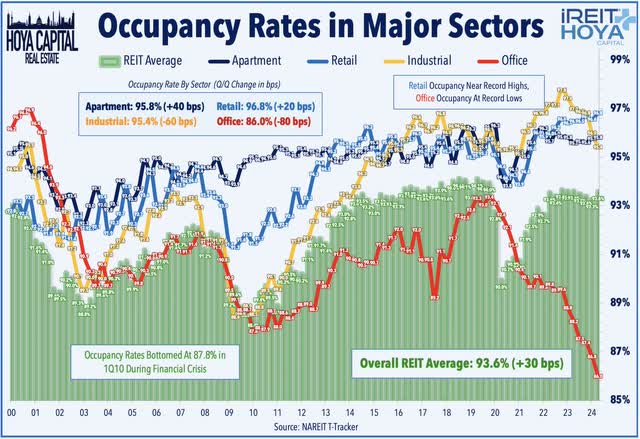

After recording the largest year-over-year decline on record in 2020 – which dragged the sector-wide occupancy rate to 89.8% – REIT occupancy rates have rebounded since mid-2020 back to 93.6% – toward the upper-end of its 20-year average of 90-94%. By comparison, occupancy levels dipped as low as 88% during the Financial Crisis and took three years to recover back above 90%. Retail REITs have been the noted upside standout on the occupancy-front, as store openings have significantly outpaced store closings over the past three years – a sharp departure from the “retail apocalypse” trends of the 2010s. Residential REITs have continued to report near-record-high occupancy rates in recent quarters – despite record levels of multifamily supply growth. Industrial REITs reported a moderation in occupancy rates to around 96% in Q2 from their record highs of nearly 98% in late 2022. Office REIT occupancy, meanwhile, has seen substantial declines since the start of 2020 and remained 500 basis points below pre-pandemic levels at 86.0% in the second quarter.

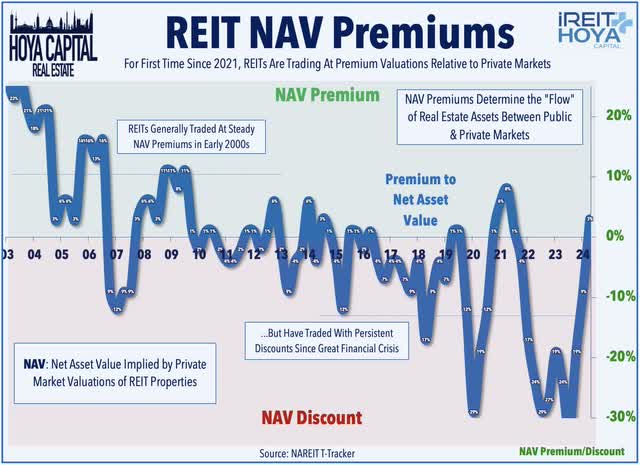

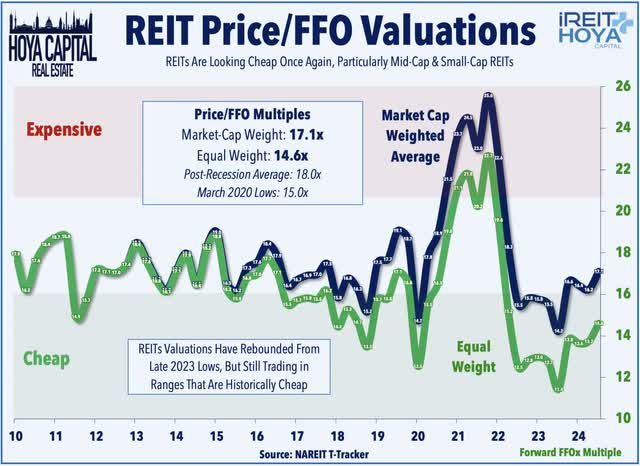

Deeper Dive: REIT Valuations & Growth

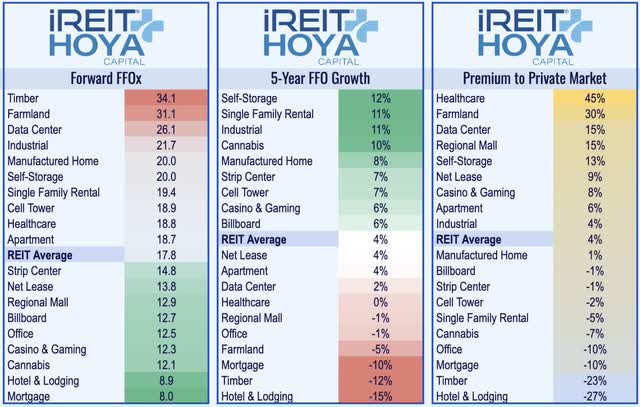

The extended sell-off from late-2021 through mid-2023 – combined with the nearly 20% increase in FFO during this time – pulled REIT valuations to the lowest level since the end of the Great Financial Crisis, but REITs aren’t quite as “cheap” now as they were at the end of June. For REITs, being “too cheap” can be a problem. Over most long-term investment horizons, “cheap” REITs tend to stay cheap via underperformance, and “expensive” REITs tend to stay expensive via outperformance. Valuations are a reflection of these REITs’ cost of capital: highly valued REITs have access to cheap capital, while cheaper REITs must pay more to access capital. While modern equity REITs are more “dynamic” than a conventional bank, these “spreads” between cost of capital and return on capital are still critical. Further, equity valuations can and do play an important role in the ability of REITs to grow accretively: when REITs trade at persistent discounts to their private market-implied Net Asset Value (“NAV”), the “flow” of real estate tends to be from public markets and to private markets. Alternatively, when REITs trade with NAV premiums, the flow is positive- REITs are able to accretive acquire private market assets.

Lifted by the recent rally since early July, the average REIT now trades at an estimated 5% premium to its Net Asset Value – as implied by current private market valuations – the first time REITs have traded at NAV premiums since late 2021. Equity REITs currently trade at an average forward Price/FFO multiple of around 17.8x using a market-cap weighted average, which is roughly only slightly below the post-GFC average of 18.0x. The market-cap-weighted average, however, is somewhat distorted by the massive weight of richly-valued technology REITs, and on an equal-weight basis, REITs trade at a 14.5x median P/FFO multiple, which is near the lowest levels since the early 2000s. Equity REITs pay a dividend yield of 3.9% on a market-cap-weighted basis, but this dividend yield climbs to over 5.7% on an equal-weight basis, and roughly 8.5% when including mortgage REITs.

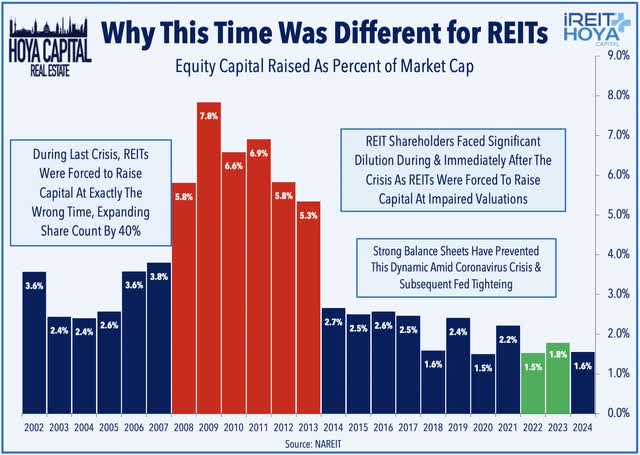

Deeper Dive: REIT Balance Sheets

The ability to avoid “forced” capital raising events has been the cornerstone of REIT balance sheet management since the GFC – a time in which many REITs were forced to raise equity through secondary offerings at “firesale” valuations just to keep the lights on, resulting in substantial shareholder dilution which ultimately led to a “lost decade” for REITs. While REITs entered this tightening period on very solid footing with deeper access to capital, the same can’t necessarily be said about many private market players that rely on short-term borrowing or continuous equity inflows to keep the wheels spinning. Much the opposite of their role during the Great Financial Crisis, many well-capitalized REITs are equipped to “play offense” and take advantage of compelling acquisition opportunities if we do indeed see further distress in private markets from higher rates and tighter credit conditions.

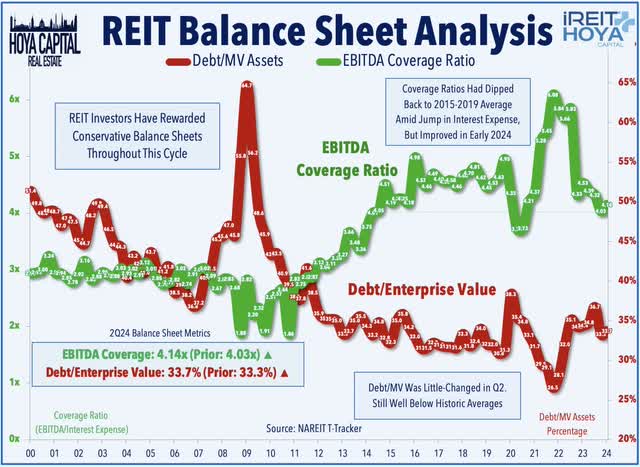

Even as benchmark interest rates doubled from a year earlier and even with market values of REITs lower by 20-30% during that time, REITs balance sheets remain healthy by historical standards, merely giving back the incremental pandemic-era improvement. Debt as a percent of Enterprise Value still accounts for less than 35% of the REITs’ capital stack, down from an average of roughly 45% in the pre-recession period – and substantially below the 60-80% Loan-to-Value ratios that are typical in the private commercial real estate space. Interest coverage ratios (calculated by dividing EBITDA over interest expense) have seen a shaper erosion over the past several quarters from its all-time highs set last year, however, but still stand at 4.1x, which roughly matches the coverage ratio at the end of 2019 and compares very favorably to the 2.75x average in the three years before the GFC period.

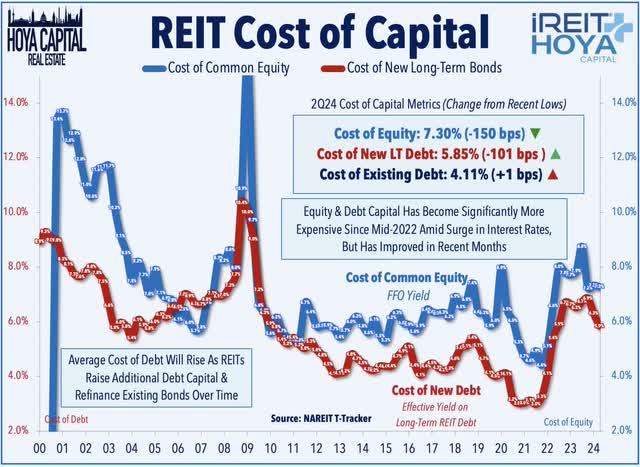

That said – not all REITs are created equal, and the broad-based sector average does mask some of the intensifying issues in several of the more at-risk sectors and among REITs that have been more aggressive in their balance sheet management. A handful of small and mid-cap REITs – some of which would be considered as having a rather strong balance sheet relative to similar private equity portfolios – have incurred significant charges to “fix” their floating rate debt exposure, while others have continued to roll the dice by maintaining a sizable chunk of variable rate debt. The BofA BBB US Corporate Index Effective Yield – a proxy for the incremental cost of real estate debt capital – has surged from as low as 2.20% in late 2021 to as high as 6.67% at the October 2023 peak and now sits at 5.12%. On a percentage basis, this represents a nearly 200% increase in interest costs on variable rate debt. The cost of equity – which we compute based on average FFO yields – is now 7.3% for the average REIT, up from a low of 4.4% in late 2021 but down from a peak of nearly 9% at the “bottom” of the REIT selloff in late 2023.

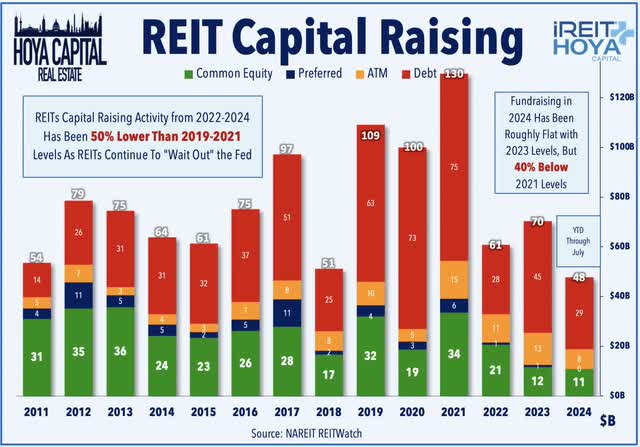

So naturally, REITs “hunkered down” in recent quarters as stock price valuations remained low by historical standards and in relation to private market-implied valuations but have started to rebound in recent months. S&P reported this month that REIT capital-raising activity surged in July as interest rates pulled back. On an annual basis, the amount of capital raised in July shot up 57% from a year earlier, which pulled the full-year total to roughly even with 2023 after a sluggish start. Through the first seven months of 2024, REITs have raised $48B in capital through equity and debt offerings. The majority of the capital raised over the last two years has been through debt offerings, which have accounted for roughly 65% of the total capital raised this year – above the historical average of around 50%. The largest common equity offering of 2024 has been the Lineage Logistics (LINE) $4.4 IPO, followed by the American Healthcare’ (AHR) $773M IPO. Industrial REIT Prologis (PLD) has been the most active with $3.88B in capital raising, followed by cell tower REIT American Tower (AMT) with $2.38B raised. By property sector, industrial REITs have accounted for the largest share of total capital raised year to date, followed by data center and healthcare REITs.

REIT External Growth: Animal Spirits Awaken?

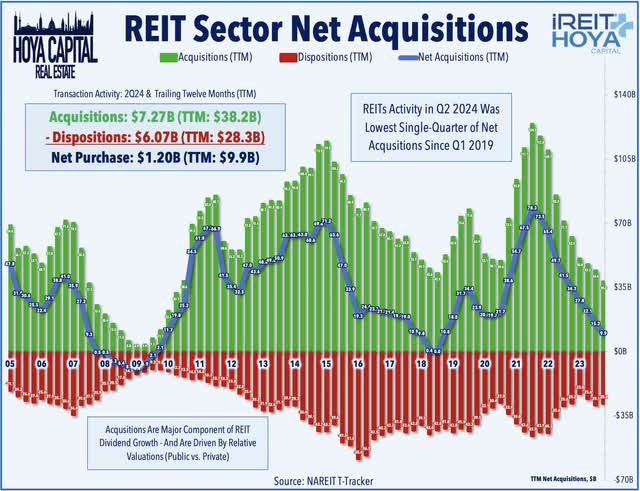

Distress for some is an opportunity for others, and we’ve begun to see – on a limited scale – public REITs with balance sheet firepower start to take advantage of capitulation from highly-levered players – a trend that will gather steam if debt markets remain tight. REIT external growth comes in two forms – buying and building. Acquisitions have historically been a key component of FFO/share growth, accounting for more than half of the REIT sector’s FFO growth over the past three decades, with the balance coming from “organic” same-store growth and through ground-up development and redevelopment. With a historically large “bid-ask” spread for private real estate assets, REITs have slowed their acquisitions over the past several quarters, with gross purchases of only $1.2B in the second quarter – the second-lowest since Q4 of 2018 – following a total haul of just $700M in the first quarter, but we believe that opportunities should emerge if debt markets remain tight.

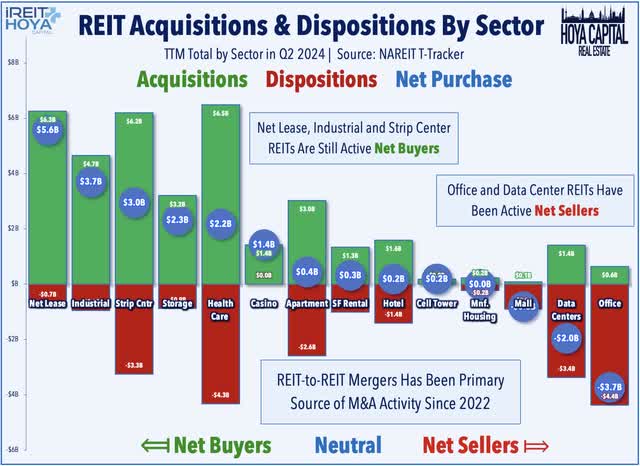

At the property-sector level, net lease, industrial, and strip center REITs have been the most active acquirers of private market assets in recent quarters – accounting for more than half of total net purchases across the REIT industry. Most other REIT sectors have been more reluctant to “hit the bid” on slow-to-adjust private market valuations. Data Centers and Office REITs have been the most significant “net sellers” over the past year. Many of the largest REIT acquisitions have emanated from Blackstone’s (BX) nontraded fund, BREIT, which has faced a wave of investor redemption requests, prompting the need to raise capital to meet withdrawals. Since December 2022, BREIT has sold over $10B in assets to public REITs, including its most recent $1B sale of an 11-building apartment portfolio to Equity Residential (EQR) earlier this month, and a $1B sale of an industrial portfolio to Rexford (REXR) in march. These deals follow a $5.5B sale of two Las Vegas casinos to VICI Properties (VICI) in 2023, an $800M sale of a Texas resort to Ryman Hospitality (RHP), a $2.2B sale of Simply Self-Storage to Public Storage (PSA), and a $950M partial sale of The Bellagio casino to Realty Income (O). Of note, these deals have closed within four weeks, on average, a remarkably swift transaction timeline that few other entities besides public REITs could pull off.

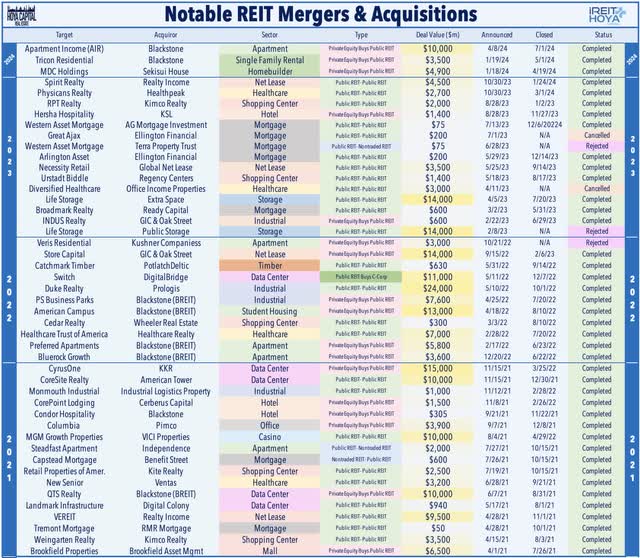

While Blackstone’s BREIT has been a net seller, the private equity giant’s other funds have continued to scoop up public REITs this year, acquiring another pair of residential REITs – Tricon Residential and Apartment Income – earlier this year for a combined $14B. From 2020 through 2024, Blackstone and its affiliates acquired nine public REITs with a combined enterprise value of over $100B, paying an average premium of 35% relative to these REITs’ prior closing price. Outside of these Blackstone-involved deals, M&A activity within the REIT sector has been almost non-existent in 2024, which followed a modest uptick in 2023 via a wave of public REIT-to-REIT mergers. Last year’s merger wave was headlined by net lease REIT Realty Income’s acquisition of Spirit Realty, healthcare REIT Healthpeak‘s (DOC) acquisition of medical office REIT Physicians Realty, and Extra Space’s (EXR) acquisition of Life Storage. We also saw two smaller-scale consolidations in the strip center space: Regency Centers (REG) acquired small-cap Urstadt Biddle, while Kimco Realty (KIM) acquired mid-cap RPT Realty.

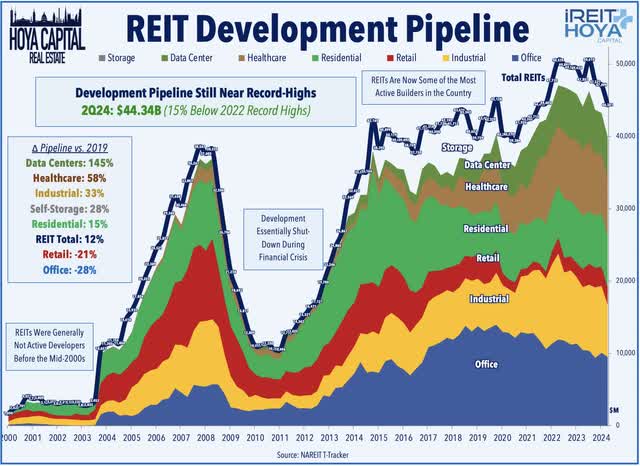

REITs have become some of the most active builders in the country over the past decade and – despite the slowdown in recent quarters – REITs still have nearly $45B of active development in the pipeline. Favorably, much of this pipeline is in the final stages of construction, as new groundbreakings have been few-and-far-between over the past few quarters given the unfavorable rate environment. The swelling of the development pipeline to the record-highs seen in 2023 was fueled by three property sectors – data center, industrial, and self-storage – which have expanded their pipelines by 145%, 33%, and 28%, respectively, since the end of 2019 – and some of this inflated pipeline is the result of higher construction costs and lingering supply chain delays that prolong the development timeline. Retail REITs, on the other hand, have engaged in minimal development activity over the past several years – which has fueled the recent occupancy increases – while the pipeline in office has also pulled back materially over the last several quarters, as expected.

Takeaways: A REIT Revival Has Begun

Two years of persistent rate-driven pressure on the residential and commercial real estate market appears to finally be abating as the worst of pandemic-era inflationary pressures subside. Since the “pivot’ in early July, the REIT Index has outpaced the S&P 500 by 10 percentage points, during which time the benchmark 10-Year Treasury Yield has declined by roughly 60 basis points. Even with this recent outperformance, REITs still have nearly 35 percentage points of “catch-up” to do with the S&P 500, if past performance patterns between the REITs and equities persist. REITs aren’t quite as “cheap” now as they were at the end of June, but that’s not such a bad thing: premium equity valuations are the “fuel” for REITs’ external growth. These macroeconomic conditions – tight debt markets combined with premium equity valuations – are ideal for low-levered entities with access to “nimble” equity capital – conditions that maximize the true competitive advantage of the public REIT model, which these entities have been unable to exploit in the “lower forever” environment.

For an in-depth analysis of all real estate sectors, check out all of our quarterly reports: Apartments, Homebuilders, Manufactured Housing, Student Housing, Single-Family Rentals, Cell Towers, Casinos, Industrial, Data Center, Malls, Healthcare, Net Lease, Shopping Centers, Hotels, Billboards, Office, Farmland, Storage, Timber, Mortgage, and Cannabis.

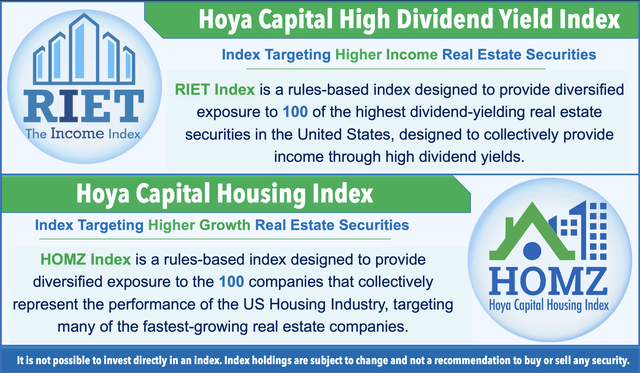

Disclosure: Hoya Capital Real Estate advises two Exchange-Traded Funds listed on the NYSE. In addition to any long positions listed below, Hoya Capital is long all components in the Hoya Capital Housing 100 Index and in the Hoya Capital High Dividend Yield Index. Index definitions and a complete list of holdings are available on our website.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.